I hope you get value out of this blog post.

Did you know that Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize-winning expert, found that people’s money choices are 90% emotional and just 10% logical?

This significant finding underscores the vital role of behavioral finance—a field that delves into the psychological underpinnings of our financial choices.

For financial advisors and coaches, understanding these emotional drivers is essential.

As a financial advisor or coach, you're no stranger to the world of numbers, spreadsheets, and forecasts.

But have you ever stopped to ponder why your clients make the financial decisions they do? Why do some of them panic-sell when the markets dip slightly, while others seem to hoard money even when they could be investing it more profitably?

The answers often lie in behavioral finance:

Behavioral finance is the intersection of psychology and finance. It seeks to explain why individuals often deviate from what traditional finance theories predict they "should" do.

Instead of portraying individuals as perfectly rational beings who always act in their best financial interests, behavioral finance acknowledges that real people have emotional and psychological biases that influence their financial decisions.

? Related: How to Communicate the Value of Behavioral Coaching

As financial advisors and coaches, going deeper into the world of behavioral finance can equip you with insights that can transform your coaching methods.

Here are some of the pivotal behavioral finance concepts you should be familiar with:

This theory, formulated by Kahneman and Tversky, suggests that people don't treat gains and losses the same way.

They often feel the sting of a loss more acutely than the joy of a comparable gain.

Example:

Imagine a client who's more upset about losing $1,000 in the stock market than they are happy about gaining $1,000. This imbalance in emotional response can influence their investment decisions.

Understanding this can help you anticipate your client's potential overreaction to losses and underreaction to gains.

It can also guide you in framing investment outcomes in a way that resonates with their psychological inclinations.

Building on the prospect theory, loss aversion indicates that people generally prefer to avoid losses rather than secure equivalent gains.

Example:

If given a choice between a sure loss of $50 and a 50% chance of losing $100, many would choose the gamble, even if it's not the most rational choice, simply to avoid the guaranteed loss.

This can explain why some clients are overly cautious or hesitant to make changes in their portfolio, even when it's logically beneficial.

This is the psychological tendency to segregate money based on its origin or its intended use.

Example:

A person might readily spend a bonus on luxury items but be very cautious with their monthly salary. Even though it's all money, the source affects their spending behavior.

Recognizing these tendencies can help you advise clients on budgeting, spending, and saving more effectively.

Some people tend to overestimate their knowledge or skills, especially in complex areas like finance.

Example:

A client might believe they can consistently beat the market because they've had a few successful stock picks in the past, disregarding the broader market context or the role of sheer luck.

Overconfident clients might take unnecessary risks. By understanding this bias, you can provide balanced advice and temper their expectations.

This refers to how people give too much weight to the initial information they come across when deciding on something.

Example:

If a client first hears about a stock when it's priced at $100, and it drops to $80, they might think it's a bargain, even if the stock's intrinsic value is much lower. That initial price of $100 becomes an "anchor" in their decision-making.

It can impact how clients perceive market valuations, investment opportunities, or financial advice. By being aware, you can ensure they consider a broader range of information.

This is the tendency to mimic the financial behaviors of the majority, often leading to market bubbles or crashes.

Example:

During the dot-com bubble, many investors poured money into internet companies not because they understood the business models, but simply because everyone else was doing it.

Helping clients recognize this bias can prevent them from making impulsive decisions during market euphoria or panic.

People tend to seek out information that aligns with their existing beliefs and ignore conflicting data.

Example:

If a client believes gold is the best investment, they might only read articles praising gold and ignore those that highlight its risks or downsides.

This can lead clients to make misguided decisions based on selective information. By understanding this, you can present a more balanced view.

Once people own something, they tend to value it more than before they owned it.

Example:

Let's say a client buys shares in Company A. Over time, even if better investment opportunities arise, the client might resist selling their shares just because they've grown attached to owning that particular stock.

This can lead to suboptimal portfolio diversification. Recognizing this can guide discussions on asset allocation.

Understanding the psychological factors that influence financial decisions can be a game-changer in your coaching practice.

Behavioral finance provides the tools to delve into these psychological nuances. Here's how you can seamlessly integrate it into your coaching sessions:

Before addressing biases, it's crucial to identify them. Every individual might have a different set of biases influencing their decisions.

Start your sessions with tailored questionnaires that can help identify these biases.

Diagnostic tools and questionnaires can be designed to present clients with hypothetical financial scenarios, gauging their reactions and decisions.

Their responses can offer insights into biases like loss aversion, overconfidence, or herd behavior.

Here are example questions that you can use to identify various behavioral biases:

| Behavioral Bias | Questionnaire Items |

| Prospect Theory | Given a 50% chance to gain $1000 or a 100% chance to gain $500, which would you choose? Given a 50% chance to lose $1000 or a 100% chance to lose $500, which would you choose? |

| Loss Aversion | Would you rather avoid a $100 loss than acquire a $100 gain? Imagine you invested in a stock that fell by 10%. Would you be more likely to sell it to prevent further losses or hold onto it hoping it will rise again? |

| Mental Accounting | Do you treat money differently based on where it came from (e.g., salary, gift, lottery)? If you received a bonus of $1,000, would you be more inclined to spend it recklessly compared to if it was from your monthly salary? |

| Overconfidence Bias | How do you rate your financial knowledge compared to the average person? (options: Below average, Average, Above average) Do you believe that you can consistently predict market movements better than financial experts or market benchmarks? |

| Anchoring Bias | If you see an item originally priced at $100 now on sale for $60, do you feel you are getting a good deal based on the original price? How likely are you to use the first piece of financial information you receive as a reference point for future decisions? |

| Herd Behavior | How often do you make financial decisions based on what your friends or colleagues are doing? If you hear of many people investing in a particular stock or asset, would you feel more inclined to invest in it too? |

| Confirmation Bias | Do you primarily seek out information that supports your existing beliefs about an investment? How often do you expose yourself to opposing views or analyses when researching financial decisions? |

| Endowment Effect | Do you value possessions more simply because you own them? Imagine you own a concert ticket that you bought for $100. If someone offers you $120 for it, would you sell it or feel that it's worth even more because it's yours? |

These questions are just starting points and can be further refined based on the actual audience of the questionnaire.

The goal of such questions is to subtly uncover biases without making the respondent overly aware or defensive about their inherent biases.

Navigating the intricate maze of behavioral finance requires not just knowledge but the right tools.

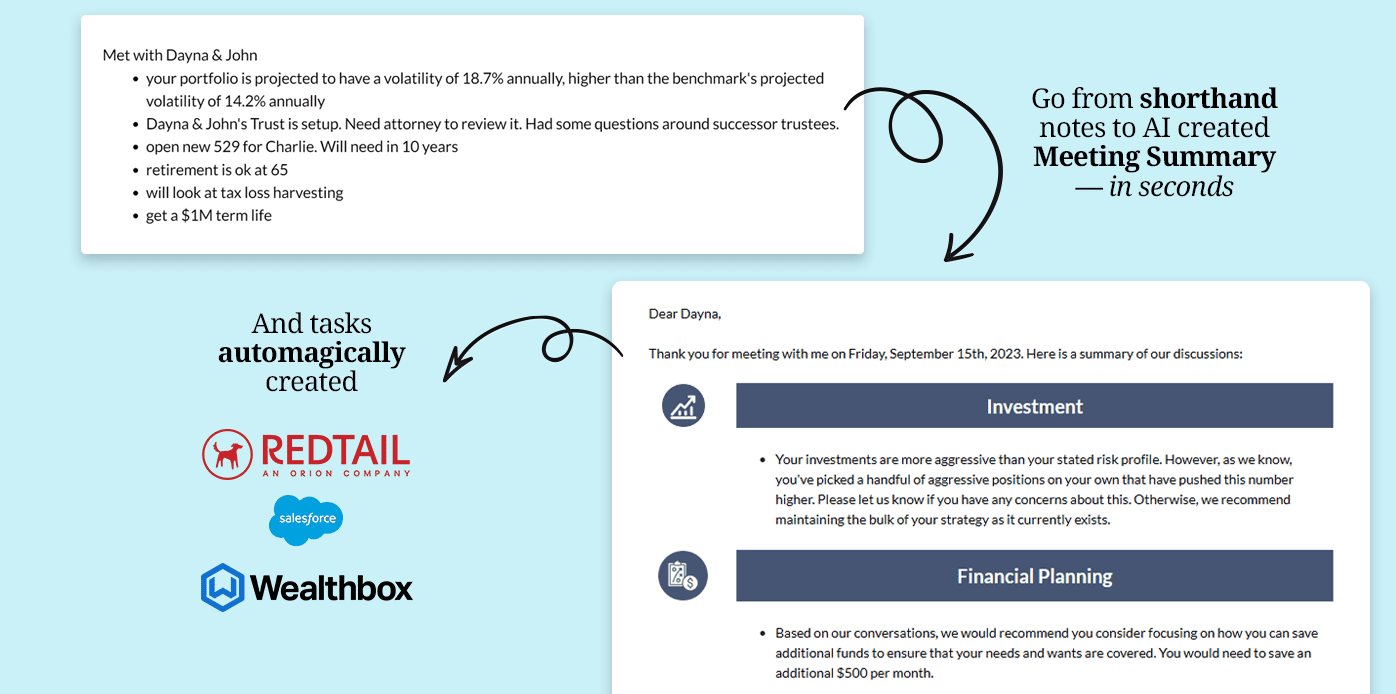

After identifying biases using diagnostic questionnaires, why not streamline your documentation process with Pulse360?

This platform is tailor-made for financial advisors, allowing you to effortlessly craft professional summaries, emails, and more.

With its AI-enhanced NoteGenius feature, you can process meeting notes 80% faster, ensuring that every insight, observation, and client detail is captured accurately.

Don't let manual documentation slow you down. Elevate your practice and impress your clients with Pulse360.

Sometimes, what clients say and what they do can be different.

As a coach, observe their reactions, hesitations, and the emotions they display when discussing certain financial topics.

Here are observational technique examples per behavioral bias:

| Behavioral Bias | Observational Technique Examples |

| Prospect Theory | Observe if the client expresses greater concern or emotional intensity when discussing potential losses compared to equivalent gains. |

| Loss Aversion | Monitor the client's body language (e.g., signs of distress or anxiety) when discussing the possibility of facing losses in their portfolio. |

| Mental Accounting | Notice if clients become more relaxed or excited when discussing "found" money (e.g., bonuses, gifts) versus regular income. |

| Overconfidence Bias | Look for signs of dismissiveness or impatience when presented with information that contradicts their beliefs or decisions. |

| Anchoring Bias | Observe if a client frequently references a specific number or price, indicating they may be anchored to that initial value. |

| Herd Behavior | Check for signs of eagerness or validation-seeking when discussing popular investments or trends their friends/colleagues are following. |

| Confirmation Bias | Detect whether the client tends to only acknowledge or show positive reactions to information that aligns with their pre-existing beliefs. |

| Endowment Effect | Notice if a client becomes more defensive or shows heightened attachment when discussing selling or parting with their owned assets. |

As with the questionnaire, this table provides a general guideline.

⚠️ Note: The nuances of each client's reactions and emotions can vary, so it's essential to approach observations with an open mind and adapt based on each individual.

Once biases are identified, the next step is to educate clients about them. Awareness is the first step toward change.

Discuss past financial events or market behaviors that showcase these biases in action.

For instance, you could talk about the dot-com bubble to illustrate herd behavior or discuss common investor reactions during a market crash to highlight loss aversion.

Here’s an example:

The Dot-Com Bubble and Herd Behavior

The dot-com bubble, which took place roughly between 1995 to 2002, was a period during which there was immense enthusiasm and speculation around the potential of the internet and associated businesses.

During this time, numerous internet-based companies, or dot-coms, were established, and many of them went public, offering their stocks to investors.

These companies received astonishing valuations despite the fact that many of them had never made a profit and had no clear path to profitability.

Herd Behavior in Action:

As these internet companies began to gain traction and their stock prices soared, a sort of frenzy took hold of the market.

The success stories from early investors in these companies led to a rush of both individual and institutional investors wanting to be a part of this "new economy".

Many believed they were on the cusp of a revolutionary shift in business and that traditional metrics of company valuation no longer applied.

The media played its role by continuously spotlighting the meteoric rises of these tech stocks, further fueling the fire.

As more and more people bought into these companies, stock prices continued to surge.

This is classic herd behavior – people were primarily making investment decisions based on what others were doing rather than grounded analyses of the companies themselves.

The Burst:

Eventually, the unsustainable nature of these valuations became apparent.

Beginning in March 2000, the bubble started to burst as confidence waned and investors began to sell off their shares.

Many dot-coms went bankrupt, and trillions of dollars in stock market value were wiped out. Those who followed the herd without a clear understanding or strategy suffered significant losses.

From my example above, it's essential to emphasize the importance of individual research and strategy over being swayed by market frenzies as an advisor/coach.

The dot-com bubble can be a reminder to clients that while it's tempting to follow the crowd, it's crucial to remain grounded in fundamental analyses and personal investment goals.

Another route you can take is engaging clients in role-playing or simulations.

Let them play out scenarios where they can see the outcomes of decisions influenced by biases versus those made rationally.

These hands-on experiences can be eye-opening, driving home the impact of behavioral biases on financial outcomes.

Here’s an example play-out scenario activity:

"Market Forecast Challenge" - Overconfidence Bias Simulation

Objective:

To highlight the dangers of overconfidence in predicting market movements and the value of diversifying investments.

Setup:

Procedure:

Repeat: Continue this for 10 rounds, simulating a decade of investing.

Debrief:

Key Takeaway:

While it's natural to trust our instincts and believe in our judgment, the stock market's unpredictability makes it challenging to consistently predict. Diversification and a long-term strategy, rather than trying to time the market, often yield better results.

This interactive exercise allows participants to see firsthand how overconfidence can lead to pitfalls in investment decisions.

The experiential nature of the activity can make the lesson more impactful than just theoretical explanations.

Identifying and understanding biases won't be beneficial unless clients have the tools to counteract them.

This is where intervention strategies come in.

Teach clients to reframe their thought processes.

For example, if a client is exhibiting anchoring bias, train them to challenge their initial beliefs, ask questions, and seek out additional information before making decisions.

Here are more examples per bias:

| Behavioral Bias | Traditional Thought Process | Reframed Thought Process |

| Prospect Theory | "I feel like the potential gain from this seems worth the risk." | "Let's weigh this potential gain against the associated risks and evaluate it in the context of my overall goals." |

| Loss Aversion | "I can't bear the thought of losing money; I need to act now." | "It's natural to feel uneasy about losses, but let's look at the long-term trajectory and the overall health of my portfolio." |

| Mental Accounting | "This bonus is extra money; I can spend it without worry." | "Every dollar has value. How does allocating this bonus align with my financial goals?" |

| Overconfidence Bias | "I've done well with my past few investments; I'm sure I can predict the next win." | "Past successes don't guarantee future results. Let's continue with thorough research and consider diversification." |

| Anchoring Bias | "This item is on sale from its original price; it must be a good deal." | "Sales can be enticing, but let's evaluate the actual value and utility of this item before purchasing." |

| Herd Behavior | "Many people are investing in this, it must be a good decision." | "Trends can be indicative, but it's essential to base decisions on individual research and my financial circumstances." |

| Confirmation Bias | "I read an article that supports my belief, so I must be right." | "It's great to find supporting information, but let's also explore opposing viewpoints to make a balanced decision." |

| Endowment Effect | "I own this, so it must be worth more than others are willing to pay." | "Ownership can create attachment. Let's objectively evaluate its market value and consider if holding or selling aligns with my goals." |

Effective reframing often requires iterative conversations and practice.

Over time, clients can internalize these reframed thought processes, making more rational and beneficial financial decisions.

Establish a protocol where clients pause and reflect before making significant financial decisions.

This could be as simple as a 24-hour waiting period before making large investments or sales. During this time, clients can evaluate their motivations, ensuring they aren't acting on impulse or biases.

Here are sample decision-making checkpoints per bias:

| Behavioral Bias | Decision-making Checkpoint |

| Prospect Theory | Before finalizing a decision, review the potential gains against potential losses using a pre-defined assessment chart. |

| Loss Aversion | Whenever feeling uneasy about potential losses, initiate a 48-hour hold period before selling an asset. During this time, revisit the long-term plan and potential market fluctuations. |

| Mental Accounting | For "found" money or unexpected income, have a waiting period of 3 days before spending. Use this time to review financial goals and appropriate allocation. |

| Overconfidence Bias | Before making investments based on recent successes, consult with an independent party or advisor. Alternatively, maintain a diary to track and review past decisions to keep one's confidence in check. |

| Anchoring Bias | When a specific price or number is fixated upon, take a step back and research a broader range of information. Set a rule to gather at least three independent valuations or opinions before finalizing a decision. |

| Herd Behavior | If considering an investment because it's trending or popular, implement a one-week reflection period. During this time, research the investment's fundamentals and seek expert opinions outside of the popular trend. |

| Confirmation Bias | Before making decisions based on supporting evidence require the reading or consultation of at least two sources that challenge the belief. A rule can be set to always play "devil's advocate" before final decisions. |

| Endowment Effect | When considering the value of owned assets, maintain a protocol to seek external valuations. Before deciding to hold or sell, consult with someone unattached to the asset. |

Incorporating these checkpoints can help clients make more considered and rational financial decisions by providing a structured approach to counteract potential biases.

Remember that integrating behavioral finance into coaching is not just about understanding biases:

But offering clients tangible tools and strategies to navigate their financial journeys with greater self-awareness and confidence.

Behavioral finance, sitting at the confluence of psychology and finance offers invaluable insights into the often irrational decision-making processes of individuals.

While traditional financial theories present a world of perfectly rational decision-makers, real-life scenarios are riddled with biases that can steer one away from optimal financial decisions.

Financial advisors and coaches equipped with an understanding of these biases are better positioned to guide their clients.

Incorporating behavioral finance into your practice requires precision, consistency, and the right tools. Pulse360 is here to revolutionize your documentation process.

With plans tailored to every need:

Why wait?

Streamline your client communications, document effortlessly, and ensure every client interaction is captured with precision.

Start with Pulse360 today and experience the difference.